TRANSFIGURING MINDANAO: Compelling Reading

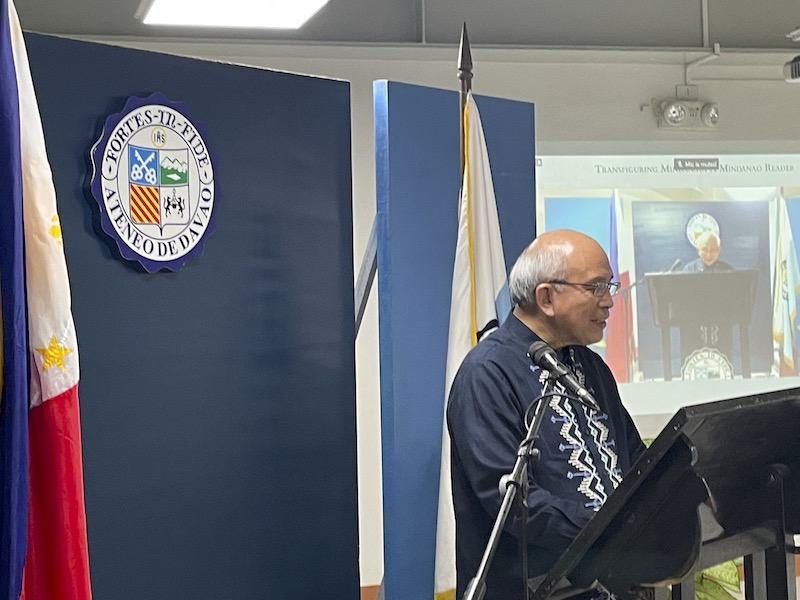

(Welcome remarks and Keynote address of Fr. Joel Tabora, S.J., President of the Ateneo de Davao University)

On behalf of the Ateneo de Davao University, I would like to welcome you all to this launch of the 788-page volume, Transfiguring Mindanao: A Reader, edited by Jose Jowel Canuday and Joselito Sescon and published this year by the Ateneo de Manila Press. It is good to finally have a book that focuses on Mindanao not merely as a subject of academic research but as a complex reality in need of transfiguration.

Part of the genesis of this book has to do with a little Jesuit history.

In 1814 the Society of Jesus was formally restored by Pope Pius VII after its suppression by Pope Clement XIV in 1773. In 2014, all over the world, Jesuits and partner communities celebrated the Bicentennial of the Restoration of the Society of Jesus. Its celebration in the Philippines allowed us to recall the return of the Jesuits to the Philippines in 1859 – 45 years after the restoration. Important for us to note today is this: the original mandate to the returning Jesuits was to evangelize Mindanao. Unfortunately, their intention to fulfill this mandate was upended by the Spanish colonial government in Manila that insisted the Jesuits remain in Manila and get involved in education. One of the major outcomes of that decision was the Ateneo de Manila University.

In the Philippine celebration of this Bicentennial of the Restoration of the Society of Jesus led by the Mindanaoan provincial superior, Fr. Antonio Moreno, S.J., this original mandate to Mindanao was part of the warrant for Jesuits in the Philippines in the course of the last decade to rethink its ministries and eventually re-commit itself as an entire Province to the mission of the Church in Mindanao. The other warrant was the visit to the Philippines of Pope Francis in 2013. During that visit, there were 40 Jesuits who were privileged to meet with him despite his busy schedule. That was in a sala of the Nuncio’s residence in Manila. I was there, thrilled to encounter this charismatic witness to the joy of the Gospel. When Fr. Moreno asked the Pope, to whom we Jesuits have a special vow of obedience, what it was that he wished of us, he answered, “Go to the peripheries. Go to the poor.” For us, it was an invitation to renewal. And to our future as a Province of Jesuits in the Philippines.

All of a sudden then the focus of all Jesuits in the Philippines was on Mindanao. For was it not fitting that they recover the original mandate to the Jesuits to work in the missions of Mindanao? And was not Pope Francis, the vicar of Christ, not in fact missioning us to Mindanao, where there were no peoples more peripheralized in the Philippines than in Mindanao? And where there were no peoples poorer than in Mindanao?

It was in this context that Jesuits and lay-co-workers from Dec. 26-28, 2013 gathered in the Finster Auditorium of this University for the Mindanao Conversations, an opportunity to brainstorm on impulses that could frame a reorientation of the Philippine Province to Mindanao. There were many: the need to address the worst poverty in the Philippines, the relentless war in Mindanao, the various calls for independence or for self-determination by Filipino Muslim communities and movements, the historical injustices wrought by the Spanish Colonizers and the Philippines State on Muslims in Mindanao, the injustice done to Mindanaoans through the homesteading and re-settlement programs under the Americans, the colonial government, and under the dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, through which the Muslims and Lumads were pushed off their lands to accommodate the Filipino settlers from the north, the alienation of the Mindanao economy from the peoples of Mindanao to favor the national economy or the private interests of actors benefitting from the national economy, the destruction of the once vast forest resources of Mindanao, the new major threats to the Mindanao ecology presented by large-scale open-pit mining.

The impulses of the Mindanao conversations were further discussed by a Committee on the implementation of the Mindanao Conversations and which eventually formulated a proposed Philippine Roadmap to Mindanao.

An early proposal for the Roadmap to Mindanao formulated in 2015 states in the context of a general commitment to new evangelization, to fight poverty and inequality, and to protect the environment:

“The impelling vision emerging from this Kairos moment would be to respond with the whole Province boldly and creatively to the immediate and pressing apostolic challenges of Mindanao, still as a whole on the Philippine periphery. This includes the ongoing resolution of the conflicts and wars in Mindanao due to injustice to Moro identity, Moro Political Sovereignty, and Moro Integral Development in the impending Bangsamoro, the exploitation and displacement of indigenous peoples for the political and economic interest of others, the pressing need for basic education especially of the Moro peoples within the Bangsamoro territories and indigenous peoples of Mindanao (Lumad), the need for religious education for the Christian populations in a plural society, the need for on-the-ground dialogue of life with communities of Muslims and Lumads, the need for inter- and intra-faith dialogue in Mindanao, the need for the use of business, information technology, engineering, science and technical-vocational faculties and facilities to create wealth through commerce, the use of commerce and business to strengthen inter-cultural dialogue and civil structures of dialogue and peace, for the promotion of an economy that does not exclude, for the promotion of a culture among cultures that respects and protects the environment, etc.”

It is in this context that Fr. Roberto Yap, current president of the ADMU (Ateneo de Manila University) and immediate past president of Xavier University in Cagayan de Oro, writes in the Foreword to our book:

“In 2016 the Philippine Province of the Society of Jesus made a deliberate decision to focus its apostolic mission, energy and resources in Mindanao. It was an acknowledgement of and a response to the sad reality in the region: the continuing poverty of its people, especially the Muslim and Lumad communities, the decades-long violence and armed conflict between government and rebel groups and the uncontrolled exploitation and degradation of its natural resources and environment, which are integral to sustaining cultures and lives of its Indigenous peoples” (xi).

He states further: “The urgency of responding to the problems of Mindanao cannot be overemphasized.”

Indeed, the editors acknowledge that through a CHED (Commission on Higher Education) grant, “a conference gathering a selection of historians, economists, political scientists, psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists, and other social scientists was organized at the Ateneo de Davao University to discuss the state of the art of Mindanao studies on Sept. 12-13, 2018. The study conference forged the idea of producing a Mindanao reader, with a vision of expanding beyond the academe to include practitioners, advocates, and other knowledge bearers in consonance with the transdisciplinary principle of dissolving the boundaries between conventional academic disciplines and the wider sources of understanding and real-world concerns. We thank Christian Pasion, Kevin Bano, and Frederic Cruz of the Joint Ateneo Institute for Mindanao Economics [JAIME, headed pro bono by Prof. Germelino “Boying” Bautista of the ADMU] at the Ateneo de Davao University for graciously hosting the conference. Mildred Estanda and Ritchell Abordo, both authors of this reader, played instrumental roles on behalf of the Ateneo de Davao Department of Economics and in collaboration with JAIME in seeing through the success of that crucial September 2018 conference.” It was as a result of the Mindanao Conversations of 2013 that Prof. Boying Bautista began his important work of studying thematically the economy of Mindanao through JAIME.

I will not attempt to present the structure and content of this reader. There will be opportunity for this in the presentations in this launch by the editors and a selection of the distinguished contributors. Let me however express my personal satisfaction that among the 41 contributing authors to this reader are Ma. Ritchel Abordo, Mildred Estanda, Gail Ilagan, Mansoor Limba, Neil Ryan Pancho, Albert Santos, all of the Ateneo de Davao. Also Bro. Karl Gaspar, CSSR, whom we recognize as one of ours through the standing partnership between ADDU’s theological faculty and the St. Alphonsus Theological and Mission Institute (SATMI). I am also delighted to find here important contributions to understanding the Muslim reality in Mindanao by partners in dialogue such as Sheik Mahir Gustahan, Yusuf Roque Morales, Darwin Absari, and, of course, our Mansoor Limba.

Let me close however by saying that I know of no other collection of studies that could better situate the serious person desirous of understanding, studying, and engaging Mindanao than this one. For a University such as ADDU that partially understands its identity to be Filipino “in the service of Mindanao” and its mission to engage the Bangsamoro people and the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) and Mindanao’s Indigenous Peoples (Lumad), this volume should be compulsory reading for its treatment of the Mindanao reality, which its editors and authors agree is complex and resistant to intellectual systematization. Indeed, it should be a reader that allows scholars, politicians, and change agents to engage Mindanao, participate in its “transfiguration,” and produce other such readers.

For me, it is also a reader to help Jesuits and their co-workers who have embarked on the Road to Mindanao to stay the course, no matter the pandemic and shifts in political landscape. The mission to Mindanao must be discerned not in the decisions of superiors 163 years ago nor even in the decision seven years ago to mission the Philippine Jesuits to Mindanao, but in the complex realities today of religious and cultural diversity, social injustice, historical injustice perpetrated by the State, if not also by the Church, against the Muslim peoples in Mindanao, of environmental exploitation, and of ongoing alienation of Mindanao from Mindanaoans that are addressed in this book. The mission of the Pope Francis to “Go to the peripheries. Go to the poor” remains compelling.

Indeed, Transfiguring Mindanao is compelling.

No comments:

Post a Comment