SPECIAL REPORT: Samal-Davao bridge affects corals, may turn fisherfolk into delivery riders

ISLAND GARDEN CITY OF SAMAL, Davao del Norte (MindaNews / 16 December) — The construction of the P23 billion bridge linking the Island Garden City of Samal and Davao City is threatening the lifeblood of Paradise Reef and fisherfolk who fear they may end up as delivery riders.

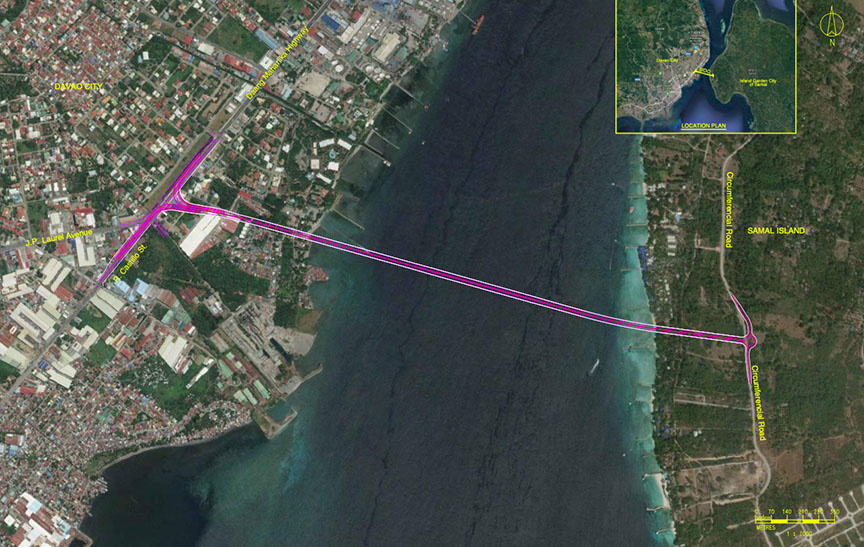

The 3.98-km, four-lane Samal Island-Davao City (SIDC) Connector Project has fueled concerns about its impact on the 7,500-sq m coral reef system, home to eight seagrass species, 118 species of corals and 73 fish species, and on the livelihood of the fisherfolk.

The project, which consists of the bridge, viaduct, and roundabout junction in Samal and Davao, is 90-percent funded with China’s official development assistance (ODA) amounting to P19.32 billion, and the rest by the Philippine government.

The loan from China carries an interest rate of 2 percent per annum and is payable over 20 years, inclusive of a seven-year grace period, according to the Commission on Audit’s report in 2022.

For fisherfolk like Tony Omayan, a Moro datu who has lived in Barangay Caliclic for 45 years now, the sea has been an abundant source of danggit (Pinspotted spinefoot), tamban (Indian sardine; Sardinella longiceps), bolinao (anchovy; Neostethus thessa), bilong-bilong (silvery flatfish) and turnos (spotted scad).

With the installment of a crane in the gulf, Omayan fears that their livelihood will be hampered, although he admitted “only time will tell” how.

“Wala ta kabalo, pero sentido kumon na nga kung naay aktibidad nga duol sa dagat, ang una mo-react ana, ang isda. Ang among isda, daghan pa siguro ron, pero kakita nami nga medyo gamay na ang mga hitsura sa isda” (We don’t know, but it’s common sense that when there is an activity near the sea, fishes will be first to react. We still have abundant supply now but we observe that the fishes are getting smaller in size), he explained.

Government, he said, should provide support for the fisherfolk, including skills training for alternative jobs, Omayan said.

“Managat pa man sila. Pero menos na ang kita. Ngano man? Tungod kay siyempre, istorbo man gihapon na, kay mangagi ang dagkong mga sakyanan, madungog man gyud na didto sa sulod [sa dagat], masamokan, ang isda makuratan, mopalayo,” he said. (The fisherfolk will continue to fish. But we expect less earnings. Why? Because when vehicles pass the bridge, the fishes below will hear that, they will be disturbed and will go away).

Omayan’s sister-in-law, Zor, 45, said the fisherfolk in their village might shift to other jobs, such as delivery riders using their motorcycles.

“Some people I know are now trying to earn money, to save money so that they would buy motorcycles — maybe they would use them in the future should we earn very less from fishing,” Zor said.

Except for some right of way issues, the “coast is clear” for the project’s completion in 2028, said Dean Ortiz, spokesperson of the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH).

On environmental concerns, he said: “We are only following to the dot whatever the DENR (Department of Environment and Natural Resources) has recommended.” DPWH, however, has put in place safeguards such as debris catchments to minimize its impact on marine life, he said.

“We make sure that the bridge will cause minimal damage to the coral reefs,” he said.

Omayan hopes they could continue their livelihood as fisherfolk.

“Ang isda makatabang as health sa tao. Unta sa kanang pamaagi, makatabang mi ug ang among mga anak sa katawhan (Fish helps keep the people healthy. We hope that through fishing, we and our children can the people), he said.

The sound from the vehicles passing the bridge is not the only reason why the livelihood of the fisherfolk will be affected. The destruction of coral reefs, too.

“Where the bridge lies, you will find the truth”

A December 2022 video showing anchors being lowered from a construction barge into the seafloor near the reef alarmed Carmela Marie Santos, executive director of the Ateneo de Davao University’s environmental arm EcoTeneo.

That can “easily destroy coral cover about the size of a classroom especially when the anchor is removed and a 50-meter rope entangled in corals will have to withstand the pull in all directions of a tugboat,” she wrote in her column for MindaNews.

What’s even more alarming to Santos is the government’s denial of the existence of coral reefs in the gulf.

“Just walk through… and literally you can walk through what is now a graveyard of dead corals… under the structure they built, and all you can see are hard corals. Where the bridge lies, you will find the truth,” Santos told MindaNews in September this year.

The bridge project will cut travel time between the city and the island over Pakiputan Strait to five minutes by car, from 30 minutes by ferry.

The island is a tourism getaway famed for its pristine beaches, waterfalls and sanctuary for giant clams and fruit bat caves.

The bridge’s landing sites are at Costa Marina Beach Resort on Samal Island, and the R. Castillo-Daang Maharlika junction in Davao City.

Marine biologist Dr. John Michael Lacson reported to the owners of Paradise Island Park and Beach Resort in the city of Samal that he discovered colonies of “dead” hard corals (Acropora Hyacinthus) near their beachfront and adjacent to the bridge’s craneway.

The coral reef system is visible during low tide from the Paradise resort owned by the Rodriguez-Lucas family.

In an email to the resort owners dated November 12, Lacson said the corals died from being covered with silt and overgrown with algae.

The corals that were “crucial to the diet and economy of Samal are being destroyed” because the SIDC construction is “not taking steps to protect the environment.”

In a telephone interview on December 6, Lacson told MindaNews: “We’ve been kept silent for so long,” referring to implementing government agencies. “We know, and you know, that there are corals there,” he said, adding “they (agencies) lie too much.”

Vital to survival

Lacson said the coral reefs are home to various species of fishes and other aquatic species, such as the presence of threatened Tridacna species, or giant clams, which indicates that “Paradise Reef is already a de facto protected area.”

In his study published in 2022, a copy of which was sent to MindaNews, Lacson identified and confirmed “indicator species” in Paradise Reef — measured by the diversity of species which can be seen, the number of species, and a “representation of adequate habitat and a healthy food web” which can be found inside the area.

To verify a marine ecosystem, Lacson only photo-documented species during his dives without using any apparatus, so that the “reader can see the reef exactly as viewed by a skin diver.”

As a conclusion to his study, Lacson said Paradise Reef must be protected due to its highly biodiverse and mature colonial structures of corals.

“The evidence provided herein indicates that the Paradise Reef ecosystem is vital to the survival of coral reef communities fringing Samal Island. Without protection of the species’ gene pools, corals and coral reef fish populations will become threatened and, eventually, endangered,” Lacson said.

“Irreversibly, irreparably and incalculably”

As early as 2019, a study by marine biologist Filipina Sotto showed that if construction work would pass through the area, it could destroy the marine environment and coral reefs “irreversibly, irreparably and incalculably.”

The area lies within the core-growth triangle in Davao Gulf and the island is recognized as a protected area under the National Integrated Protected Area System (NIPAS), according to her study.

Protected Area refers to “ecologically rich and unique areas and biologically important public lands that are habitats of rare and threatened species of plants and animals, biogeographic zones and related ecosystems.”

“In constructing bridges, the landing site where the main bridge and its approach viaduct will be constructed must be given utmost consideration,’’ Sotto said in her study.

“It is inevitable that during and after the construction of the bridge, the benthic communities will be irreversibly, irreparably and incalculably destroyed by such bridge, infrastructure or development projects,” she added.

On top of the water, air and noise pollution that the project is creating, owners of the Paradise resort have also opposed the structure’s alignment for fear it would damage the Paradise Reef.

“I am not against the bridge. We are supporting the bridge… [Our issue] is really more on the location because we are really trying to protect the reef that we have,” said resort manager Julian Rodriguez.

DPWH spokesperson Ortiz maintained that the current alignment of the bridge lies outside the NIPAS.

Ortiz also said “he had already seen” the water beneath the bridge, and emphasized that there are “little to no coral reefs.”

DENR – “Little” corals detected

In 2021, the DENR assessed the coral reef in the area and came up with some observations: high denomination of rubble, sand, and silt; blocks of cement; patches of hard corals; turbid water produced by strong underwater current; and cellophane and plastic materials.

After testing three locations in waters off Barangays Limao and Caliclic, DENR assistant regional director Victor T. Billones concluded that their hard coral cover was in “poor condition.”

This belied environmentalists’ findings that the area had living coral reefs before construction began, and paved the way for the issuance of an environmental compliance certificate for the project in 2022.

Ma. Mercedes Dumagan, DENR director in Region 11, has yet to respond to MindaNews’ requests for comment. MindaNews sought her comment thrice in November and December.

“No objection”

From 2022 to 2024, the Davao City council conducted a series of hearings on calls to halt the project, which saw government agencies defending it from criticisms that it would adversely affect Paradise Reef.

In one such hearing on January 18, 2023, Raul Millana, then regional director of the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, said the agency had “no objection” to the project, “and if even the corals will be damaged, it is possible to restore these reefs through modern technology.”

In the same hearing, Bagani Fidel Evasco, executive director of DENR in Region 11 from November 2020 to July 2023, said the reef “will not be directly affected by [the] putting up of bridge columns… but vibrations from construction will reach the reef.”

He said Paradise Reef only contained “rubble with observable patches of soft corals… but [there were] no observable corals.”

Evasco further added that the reef can be recovered in less than a year, through coral budding, or propagating corals using their own “bud,” to grow and form a bigger colony of corals.

City Councilor Temujin “Tek” Ocampo, chair of the committee on environment and natural resources, closed the hearings in September this year.

MindaNews obtained a copy of the committee report on the hearings last September 18.

The “SIDC is a national project… and any specific environmental concerns must be escalated to the appropriate government agencies, such as DENR or in proper courts,” he was quoted in the report as saying.

Sought for comment, Ecoteneo’s Santos said: “There is a centennial table coral there that was lost. Can you recover 100 years in one year?” (Ian Carl Espinosa / MindaNews. Reporting for this story was supported by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network in partnership with Lyf and Philippine Network of Environmental Journalists)

No comments:

Post a Comment